In 1992, I was a few years out of college, living in my first solo (studio) apartment, working at an unglamorous but rewarding-ish job, and agonizing over romantic travails that in retrospect were mostly self-induced. All perfectly normal for an early 20-something.

I also happened to be living in a time when women my age were suddenly getting record contracts and radio airplay with raw, honest songs they’d written about societal expectations, self-doubt, the men who’d done them wrong, their longing for love clashing with their need for independence—which just happened to be things I was wrestling with myself.

And none of them spoke to me more personally than Tori Amos.

For a rule-following, good girl like me, Amos was just the right amount of weird. Her hair, dyed a defiantly fake orange, made a statement, but she wore everyday jeans and tank tops. She played piano—not guitar—yet attacked the keys with rambunctious, rock-star energy. Her smile was warm and generous; she gave off arty-but-not-full-of-herself vibes.

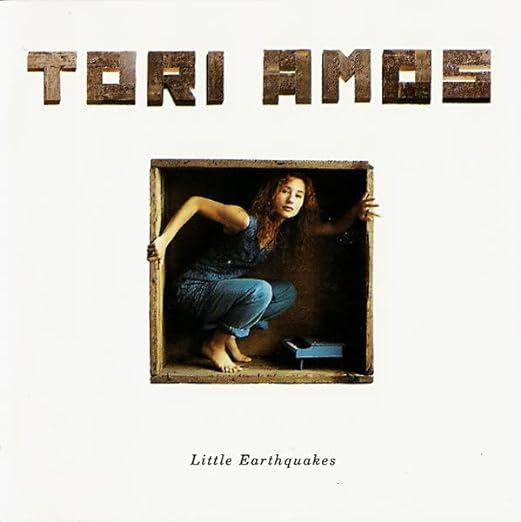

And my God, could she sing. On her debut album, Little Earthquakes, Amos’s voice swooped from operatic highs to growling lows, from the jauntiness of old-fashioned music-hall ditties to a gripping monotone. Little Earthquakes was all over the place, in a good way, switching tone and mood with every track.

Which is exactly how I felt some days.

The songs that spoke to me most had what I can only describe as grandeur, the dramatic piano chords and Amos’s commanding voice making them sound majestic and important—even when the lyrics were describing what some would consider the trivial interior lives of young women.

Sometimes I hear my voice and it’s been here, silent all these years

There are pieces of me you’ve never seen, maybe she’s just pieces of me you’ve never seen

Give me life, give me pain, give me myself again

Amos sang about the lingering trauma of school bullies (I want to smash the faces, of those beautiful boys, those Christian boys/ So you can make me cum, that doesn’t make you Jesus). She sang about being a happy ghost who’d forgive the “atrocities of school,” as she went “chasin’ nuns out in the yard.”

The album’s most infamous track was “Me and a Gun,” an a-cappella account of the thoughts that go through a woman’s mind as she’s being raped. Amos openly acknowledged that it was inspired by personal experience, a rare and brave confession for a female celebrity at the time. (It also made her a beloved advocate and role model for sexual-assault survivors.)

But I usually skipped past that track when I played the CD. As a young woman living in a big city, I spent enough time looking over my shoulder when I walked down a dark street; I didn’t need to be reminded that it could one day, possibly, happen to me.

The songs I liked best weren’t so straightforward. While rooted in recognizable emotions and relationships, they branched off into mysterious allusions, more stream-of-consciousness poetry than storytelling.

What if I’m a mermaid in these jeans of yours with her name still on them?

That line, from “Silent All These Years,” doesn’t make logical sense. I still don’t know what it means. But as a young woman, I felt the emotions embedded in those words: the wish to transform into someone/something more beautiful; the ache of jealousy.

And for millions of young women like me, Tori Amos showed that our everyday uncertainties and resentments could be turned into art.